Travel report Ukraine 07/2024

Dear friends of the Csilla von Boeselager Foundation,

Last week I travelled to Ukraine again to gain a better understanding of the situation, to further sharpen our work there, to encourage our partners in Odessa and to be able to report first-hand to you, our loyal donors. I have accompanied indescribably wonderful and committed people there in their work and on their field mission.

My conclusion: we are in the right place at the right time. What we have been able to establish there through our partners has developed into what is now the strongest of the regional aid organisations: "New Dawn". I can also say this because I was present at the regional meeting of OCHA (UN Organisation for Coordination of Humanitarian Aid) and spoke to many of those responsible.

I am incredibly grateful that I was able to experience and accompany the team there - and I can personally promise you that your donation is well invested here (this of course also applies to our other projects in Ukraine).

Field Mission Kherson

Kherson was occupied by the Russians until last year. The city has now been liberated, as has the northern part of the district. There are still 140,000 people living here who do not want to leave their homes and villages. The Russian army is just on the other side of the river. We drove deep into the so-called grey zone to bring relief supplies. Only a few aid organisations are allowed into this zone, especially after two employees of a French aid organisation were recently killed. Russia has declared the aid organisations to be the enemy because they are helping to prevent the occupation. I am travelling with well-trained people, there is strict security protocol with heavy protective waistcoats and helmets, but we take off our helmets to distribute the aid - it seems inhumane.

In Sofivka, we are very close to the front line - you can see the other side of the river, which is still occupied by Russia. The distribution of relief supplies is organised and everyone has to sign. Some laugh and seem cheerful at the meeting, most are shy. They leave quickly, because crowds are dangerous. A mobile bunker that is far too small stands on the village square. It only takes 12 seconds from warning to impact, says the head of the district. He would prefer to evacuate everyone, but this is their home and at least they have some land here, they can plant something. Last year, we distributed seeds here. Project sponsor Philipp Francke has been here many times - without him, New Dawn would not exist.

We are not allowed to stay long, but I am still able to have a few conversations: The people live between fatalism and hope, they are grateful for the few relief supplies. The boy I talk to is shaking, he lost his father in May, his mother is crying - she has four children and they were finally going to get married in July. Babushka Ala, as everyone here calls her, doesn't seem to have lost her sense of humour, however; she is obviously the centre of attention for some of the villagers. One woman reports that it is worst at night: you can constantly hear the shots and muffled or loud impacts.

Before we drive back, we make a stop in Kherson city. Here we pick up used fire extinguishers with the emptied Sprinter so that they can be refilled in Odessa. A drop in the ocean, but at the moment incendiary grenades are being fired and the understaffed fire brigade barely has a chance of extinguishing the fire - so the deputy mayor asks for help with self-protection. He comes himself and helps with the loading.

On the way out of Kherson, we drive through the city centre.

I feel quite different here. The streets are empty, the houses burnt out, the asphalt cratered. There is hardly anyone to be seen of the 79 thousand people (previously 284 thousand). We drive past the Academy, a building commissioned by Catherine the Great, where bombs hit three days ago. We briefly get out for a photo on the "Freedom Square", which became famous when the city was liberated, but all we really want to do is leave - and cry. I'm not writing this to impress, but because that's how I feel at the moment.

Life at war

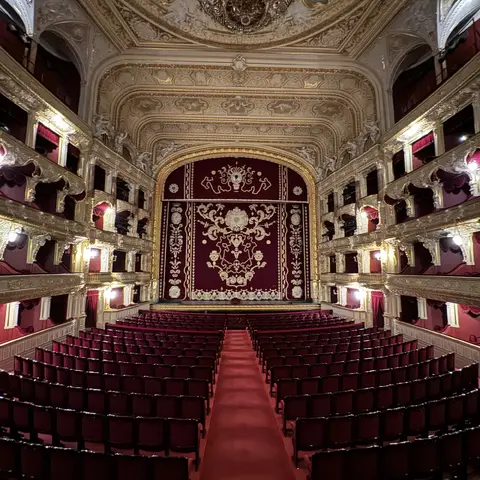

We drive back and stream the quarter-final between Germany and Spain in the car - more contrast is hardly possible, but it helps. People have to get on with their lives anyway. You can feel the stark contrast in Odessa: I go for a walk in the city with Philipp on Saturday, the shops are open, people are drinking cappuccino in the sun. I meet the director and the chief conductor of the opera, one of the most famous opera houses in Eastern Europe. They had never closed, now they even play once or twice a day. Yes, they have lost many employees to the war, says the conductor. Recruitment methods have become brutal, everyone is afraid of being found by the military. Anyone who hasn't volunteered doesn't want to go to the front - I can understand that, it's a terrible dilemma. In the evening we go to the opera with the whole team, over twenty people. "Don Pasquale" by Donizetti, an opera buffa. The director says that people need something cheerful now. Prices are ridiculously cheap from a Western point of view, but they have already doubled or tripled since the start of the war, as have food prices. People are earning less and everything is getting more expensive.

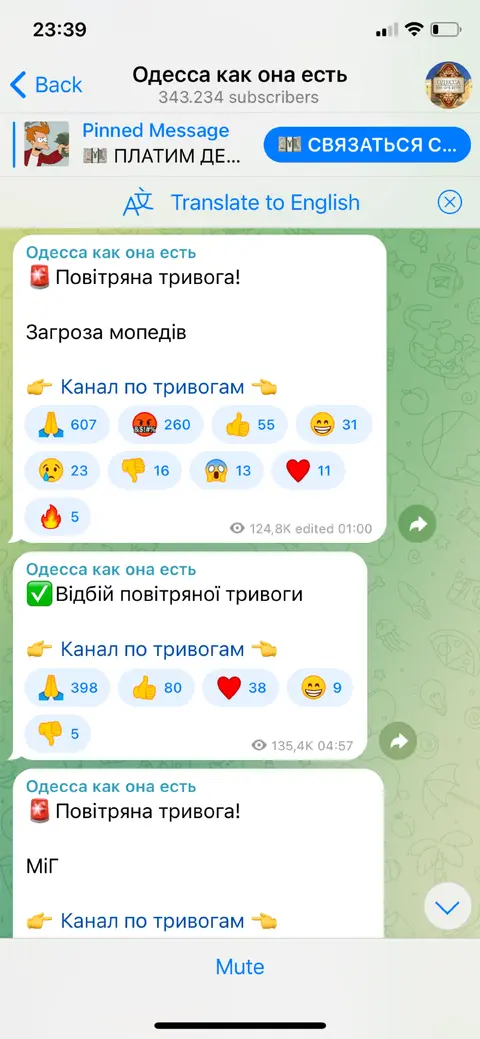

At least public order has been restored for the time being: Everything is running, from traffic controls to rubbish collection. Electricity is available half-day, otherwise the restaurants are firing up their generators. The opera has brought forward its performances to 5 p.m. - there are more bomb alarms in the evening than during the day, they have had to cancel too often.

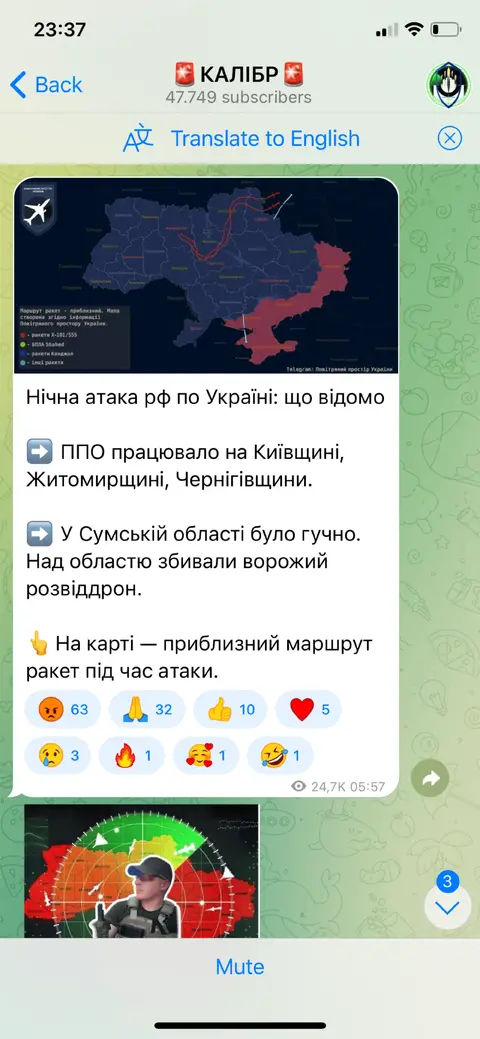

When I go to bed that evening, I read on the Telegram channel, which informs the population live about military activities, that five bombs were fired at Odessa Oblast today. I heard one while I was sitting in a café: it hit a missile defence station 50 km from Odessa. On Telegram, people are celebrating because it was a dummy that was destroyed - and showing a Russian propaganda film showing the launch and saying they fell for it. It all takes place somewhere between fiction and reality, it could almost be a mobile simulation game - but it is reality. And you're lying in your hotel room without electricity, wincing at every muffled sound. It's unlikely that you'll be hit yourself, but you know that someone almost always is.

OCHA meeting

The day before the field mission, we attend the UN First Response Meeting in Mykolaiv organised by OCHA (Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs). We meet in a basement room for security reasons, it's cramped. There are a lot of people here: Regional and international NGOs, and of course the UN organisations themselves - but they are not allowed to enter the Grey Zone. Domestic NGOs are asked to do the "last mile", our New Dawn for example. Many statistics are presented and the population is surveyed. In the first 1.5 years, every organisation did what it wanted. Get in quickly, distribute relief supplies in the first village, take photos and get out again quickly. Firstly, there were fatalities, but above all it meant that some villages had overfilled barns and others had nothing at all. In addition, well-intentioned aid often misses the mark. New Dawn has been closely liaising with the authorities and OCHA for a long time. Now, however, intensive care is being taken to ensure that aid is organised for everyone - as far as possible.

New Dawn (www.newdawn.org.ua)

I am generally impressed by how professionally New Dawn now works. There is a firm no-corruption policy. This leads to a lot of paperwork. A tender has to be issued for literally every pen, nothing works without a contract with a stamp and signatures. Everyone in need is registered, IDPs (internally displaced persons) are only allowed to come at certain intervals, depending on stock levels. There is an electronic queue so that there is less crowding. But what impresses me most are the people who work here. Almost all of them have been here since the beginning, came to help - and stayed.

Slava, for example: he had an extremely successful plumbing business in Luhansk, and because he was pro-Ukrainian, people had been giving him a hard time since 2014. But when the Russian invasion began, his life was threatened. He left almost everything behind, packing only his wife and two sons into the car with the bare essentials. As he couldn't simply drive into the unoccupied part of Ukraine, he travelled up through Russia to Estonia in March 2022 and then came back to the Ukrainian border from the other side via Poland. The customs officers were amazed, because while everyone else wanted to get out, he was the only Ukrainian car that wanted to get back in. He came to Odessa and started to help. Today, he is primarily a crisis-trained driver and brings relief supplies to the front line several times a week. He has already experienced a lot, including the vehicle behind him being hit by a deadly missile. Slava seems like a doorman and is such a kind-hearted person - just like everyone I meet here. Some of them are now permanent employees. This part of the finances is mainly provided by Johanniter International, we concentrate on projects and relief supplies - so the same applies in Ukraine: every euro you donate reaches those in need.

When I board the bus to Moldova early on Sunday morning, there are only women and children and a few foreigners on board with me. Yesterday there was another report on Telegram about fugitive young men who were caught at the border. I spoke to women who are afraid for their husbands. The whole country is in trauma. I hope and pray that peace will return to this maltreated country. Until that happens and beyond, we will continue to work and help alleviate what the invasion is doing to the people.

I ask you not to let up either. It's not about the masses, it's about individuals. I have looked into their faces. Thank you for helping us to help.

Dortmund, 8 July 2024

Dr Raphael von Hoensbroech

1. Chairman

Beitrag teilen